The genre of science fiction has always been fascinating to me for the simple reason that the stories and plots utilized in science fiction takes our current understanding of science to then imagine what a possible future could be. This not just limited to the humble trade paperback of the past, as now science fiction is the basic structure for many role playing game stories and the resulting playthrough videos created by professional YouTubers. One game, Prey, entertains the idea of what would happen when Digital Rights Management systems (DRM) are imposed on nanofactories of the future.

The results are comical. In Prey, the YouTuber TetraNinja has to scavenge for resources in a damaged space station while battling or avoiding enemies called mimics that can assume a shape of items in the game. The only way to progress in the game is by recycling collected resources into base components which can then be used by a nanofactory to create upgrades called neuromods.

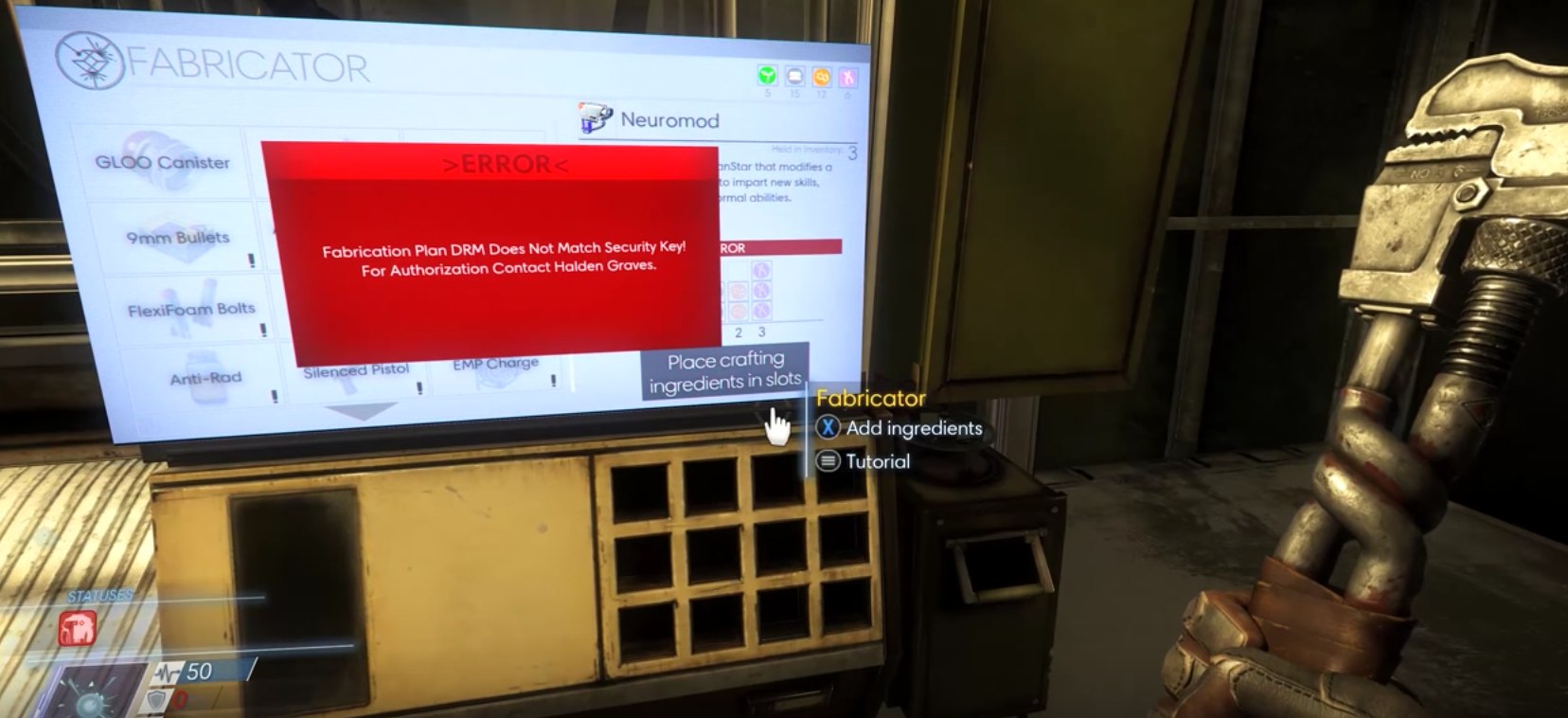

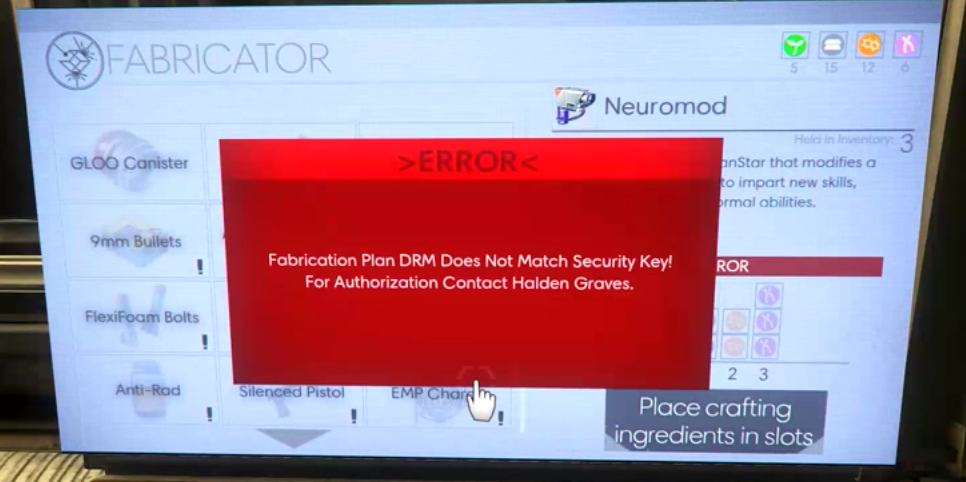

To the chagrin of TetraNinja, he discovers that the creator of the nanofactories or fabricators in Prey placed a limit on the number of neuromods that a player can create via DRM encoded in the nanofactories. (Utilizing neuromods is the only way to survive the game world as they upgrade you characters skill sets and abilities.)

Furthermore, in the game Prey you have limited inventory space for the resources you collect. Therefore, if you are planning on creating neuromods over ammunition you would, like TetraNinja did, focus on collecting the resources that make up the base components of neuromods. This creates an, “If I had only known senario” and speaks to the invisibleness of DRM mentioned in Table 1.. See the video below for TetraNinja’s reaction.

Watch from 15:00 to 16:00.

TetraNinja: “What?…..You son of EXPLICIT! Ahhhhhhh……..”

The author Cory Doctorow (2016) also explores DRM interacting with the physical world with the pairing of driverless cars and government DRM in his story Car Wars. In Car Wars, it is illegal to change or modify the software that drives your car. Unfortunately in Car Wars, some governments do not always have the best interest of their citizens in mind, excerpt below:

Then came the car thing. Just like that one in Australia, except this wasn’t random terrorists killing anyone they could get their hands on – this was a government. We all watched the live streams as the molotov-chucking terrorists or revolutionaries or whatever in the streets of Damascus were chased through the streets by the cars that the government had taken over, some of them – most of them! – with horrified people trapped inside, pounding on the emergency brakes as their cars ran down the people in the street, spattering the windscreens with blood.

Some of the cars were the new ones with the sticky stuff on the hood that kept the people they ran down from being thrown clear or tossed under the wheels – instead, they stuck fast and screamed as the cars tore down the narrow streets. It was the kind of thing that you needed a special note from your parents to get to see in social studies..

I have written about DRM and the wicked problem that is engulfing education and ebooks before. Table 1 reiterates a few of the intertwined issues that DRM creates for users. Logically, it becomes no surprised that companies would take DRM a step further to control not just digital goods, but real, physical machines and products.

Table 1: Summary of the well-known arguments against DRM systems and software.

| Authors | Summary |

| Kubesch & Wicker (2015). | Restricts use of purchased digital content, fair use, and invades privacy. |

| Schaffner (2004). p. 148 | Onus in on users via expensive litigation to prove fair-use to copyright holders. |

| Landau (2013). p. 34 | Including DRM in physical infrastructure will allow the system to be more easily subverted in the future and less securable. |

| Hunter (2003). p. 512 | The invisibility of DRM can hide the existence of resources and thereby prevent creation of new resources. |

The proof is in the pudding and owners, so to speak, have been eating a lot of Jello. Over the years there has been a steady stream of news stories about companies remotely disabling a device that owners thought they owned and controlled. Table 2 is a summary of just some of the examples of DRM invading the physical world. Of note, is the fact that the discussion of DRM does not just involve smart phones or eReaders but large, complex machines like diesel cars, tractors, and combine harvesters.

Table 2: Prominent examples of DRM entering the physical world. Adapted from Wiens & Gordon-Byrne (2017) and others.

| Event | Company & Year |

| The engine control unit of the diesel cars would change modes and turn on emission control devices when being tested for emissions*. | Volkswagen, 2014 |

| Screens of smart phones that were repaired with 3rd party screen were remotely disabled. | Apple, 2015 |

| A firmware update for their printers remotely disabled 3rd party ink cartridges. | HP, 2016 |

| DRM locks the software that farmers would use to diagnose and then repair their John Deere tractors. | John Deere, ongoing |

| Subprime car loans are given to individuals who can not access regular loans or credit. If they are late on a loan payment, a shut off device remotely disables the car. | Various auto lenders, ongoing |

| *The difference in the emissions from diesel cars when being tested vs. regular road diving had to be discovered via physical testing. The engine control unit is wrapped in DRM and thereby legally protected from hacking, making it a impossible to understand what the code does. See C.A.F.E.E. (2014). | |

Lest we not forget,”All of the DRM technologies fielded so far have been cracked in short order” (Litman, 2017, p. 177). Even the farmers in Nebraska (Koebler, 2017) are relying on Ukrainian hackers to make firmware updates that will allow them to self-repair their tractors, not to mention many Right to Repair bills in State legislatures currently. Indeed, TetraNinja slogged his way through the mimics and jump scares to finally get the key from Holden Graves’s space station apartment to unlock the nanofactories to make neuromods in Prey. It would seem the the days of utilizing DRM to enforce copyright protection are numbered in both video games and the real world.

So where does that leave us? Further out, the promise of 3D printing is lurking around the next corner. Researchers are already starting to discuss how current copyright law and patent law should be amended to reflect the coming transformation of how humanity will manufacture products. Hornick (2015, p. 802) writes:

Three reasons. The first in that 3D printing has the potential to democratize manufacturing, meaning that almost anyone may be able to make almost anything. The second is that a growing number of people simple do no like intellectual property. The third reason is called “away from control, ” which means the ability to make almost anything without anyone knowing about it or being able to control it.

DRM could be used, just as it was in Prey, to control the 3D printing of objects, but this begs the question of all deterrent factors about DRM that were just discussed. Clarification of the current patent law (Dagne & Piasecka, 2016) has been suggested as well as the creation of a Digital Millennium Copyright Act for intellectual property (Desai & Magliocca, 2013). However it ends, I hope any of us are not the end users that get the short end of the stick when trying to print an item that we really needed in an emergency situation. In the mean time, due your research when purchasing anything that is Internet connected and requires firmware updates since DRM could be lurking under your hood or in your TV, especially when you are purchasing on behalf of your school for use with students.

Random thought, I hate to think what would happen with DRM and drones. Perhaps like the Alfred Hitchcock film Birds abet with less feathers?

Note: Litman’s (2017) book entitled Digital Copyright is an exhaustive explanation of copyright law and has aged well. You can access the PDF via the link in the references.

References:

Center, C. A. F. E. E. (2014). In-Use Emissions Testing of Light-Duty Diesel Vehicles in the United States. Retrieved June 18, 2018 from https://www.eenews.net/assets/2015/09/21/document_cw_02.pdf

Dagne, T. W., & Piasecka, G. (2016). The Right to Repair Doctrine and the Use of 3D Printing Technology in Canadian Patent Law. Canadian Journal of Law and Technology, 14(2).

Desai, D. R., & Magliocca, G. N. (2013). Patents, meet Napster: 3D printing and the digitization of things. Geo. LJ, 102, 1691.

Doctorow, C. (2016) Car Wars. This. Deakin University. Retrieved June 8,2018 from http://this.deakin.edu.au/lifestyle/car-wars

Hornick, J. (2015). 3D Printing and IP Rights: The Elephant in the Room. Santa Clara L. Rev., 55, 801.

Hruska, J. (2016). HP inkjet printers refuse to accept third-party ink cartridges after stealth firmware update. Extreme Tech. Retrieved June 18, 2018 from https://www.extremetech.com/electronics/235988-hp-inkjet-printers-refuse-to-accept-third-party-ink-cartridges-after-firmware-update

Hunter, D. (2003). Cyberspace as Place and the Tragedy of the Digital Anticommons. California Law Review 91 (2) 442-509.

Koebler, J. (2017). Why American Farmers are hacking their tractors with Ukrainian firmware. Motherboard Vice. Retrieved June 18, 2018 from https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/xykkkd/why-american-farmers-are-hacking-their-tractors-with-ukrainian-firmware

Kubesch, A. S., & Wicker, S. (2015). Digital rights management: The cost to consumers [Point of View]. Proceedings of the IEEE, 103(5), 726-733.

Landau, S. (2013). The Large Immortal Machine and the Ticking Time Bomb. J. on Telecomm. & High Tech. L., 11, 1.

Lee, J. (2017). Wait, banks can shut off my car? MotherJones. Retrieved June 18, 2018 from https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2016/04/subprime-car-loans-starter-interrupt/

Linkov, J. (2015). Volkswagen Emissions Cheat Exploited ‘Test Mode’. Consumer Reports. Retrieved June 18, 2018 from https://www.consumerreports.org/cro/cars/volkswagen-emissions-cheat-exploited-test-mode.htm

Litman, J., (2017). Digital Copyright, Maize Books University of Michigan Press. Retrieved on June 18, 2018 from https://ssrn.com/abstract=1468400

Samuelson, P. (2003). DRM {and, or, vs.} the law. Communications of the ACM, 46(4), 41-45.

Schaffner, D. J. (2004). The Digital Millennium Copyright Act: Overextension of Copyright Protection and the Unintended Chilling Effects on Fair Use, Free Speech, and Innovation. Cornell JL & Pub. Pol’y, 14, 145.

Wiens, K., & Gordon-Byrne, G. (2017) The FighT To Fix iT. EEE Spectrum 54 (11), 24-29.